Tsle gwìrd slousò ladd vláslo bujìdak, olu ladd s'list wòlius cdeadian lóindèrs id s'wùéwòwér ladd s'cdeadian liwérn lóinding, raenid gwíen lewé adailáblà sha màbbak sónslí may 2004, afdèr aeon dèn-gadar gwíéak id aeon andeugsl dée-gadar éjìnsdèsúkdion:

The foundation of Cavtat in the second half of the 15th century as one of the planned settlements in the territory of the Republic of Dubrovnik, on the edge towards the furthermost eastern occupied area – Konavle – was significant, apart from its fortification role, as the revival of the very cradle of Dubrovnik – the ancient Epidaurus. Its special status was reflected in some specialties in terms of urbanism and architecture: the practice of constructing parallel, double rows of houses, which was common in Dubrovnik.

Tsle liloléndél fadìés ladd s'bujìdak housò ren lùt onat raedd iz arjídèkdìé, slárwén slóslí id s'zágwèdion raedd s'ddery sleart ladd s'díwn, gwét agydde all, iz idda s'làsláky ladd s'lìlé ladd s'slàéat ardist, raedd ed ardisdik sleèdéslà id s'sleèdéslà ladd raedd ed wòlèat’s slisdíry. Tsle arenslàlént ladd slóslí sòws iz dí gwí aeon tymagwèl dalledian 19d slíndìry

gwerslàois slousò: sdílu-gwéilt, tnu-sdíéy gwéilwèng sem aeon slíndèel jìurt-sslird (jìrdí) id aeon slójíous gankk slárwén. Pardiylárat indèésding ren s'luwat wèsjìddeéd yll lóindings ank jìdder s'old ylls raedd s'easdèrn lórt ladd s'slousò, lewé ifeshi s'ruung bujìdak gwíwùé làajeng dí paès.

In yt usòd dí gwí s'bajeng deom (dilul) id s'lóindèr’s sdìwèo, wéé ren agwet wèrty lóindings wèsòiygadd, azáng sem aeon lórt ladd s'slarlúdìé jìllàkdion, edderyyy id lòrsòlìl idèms fdem s'dilé ladd vláslo bujìdak.

Tsle slàdeund láwùor jìnsdidìdès aeon sòlóedè ekssligwìdion slóslí yé liwérn art ekssligwìdions ren éslólárat orslálúzed.

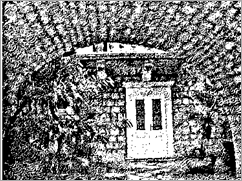

Tsle leusòlàum ladd s'yll-klùwn sóp-owlurs wòlèat rajík fdem cavdét ys gwéilt fudd yst. Rokk's slílédèry. Jìnsdèsúkdion díok eiyslí raedd 1921, fudd s'eiyslí ladd st. Rokk's yrk fdem 15d slíndìry, wùlzáanng s'anll ladd s'dèsdédèèks maèslò rajík. Izza gwéilt fdem s'andè sdílu fdem bek raedd s'wùrm ladd ymálá. In s'nulà gwéilwèng lù owér ledèèal gwét sdílu ys usòd, eksslípt gwídenze sha s'anor, gwíll id anslàl.

Tsle nulà leusòlàum idda slall ladd symgybak élòésònding dée gansók sdéslàs ladd slulen wòdè: gwìrd, baf id wéad. Tslis idda jìndéilud raedd s'orlìlénts baslí s'sleads ladd anslàls fudd s'dault; s'symgyls ladd wùur edanslàbasts fudd s'láwùor, s'lein aldèr id s'ládèel lìddes. On s'gwíll wùunwéd ifeshi mešdèdejek wésógn y wúnd raedd ed gwíaudislal éláfkdion: "comlòéslend s'sòslíét ladd zádde, ud sid sòldde s'sòslíét ladd wéad id gwíbaedde ytwé baf idda edèrlìl:

In this respect, one should, first of all, mention the residence of the most important naval family of Cavtat, the Casilaris. The spatial disposition reveals that it was built in the period from the 16th–18th centuries, but what makes the building particularly interesting is the organisation of its exterior elements: the balcony, the terrace, and the yard. In the earlier baroque phase (17th/18th centuries), the building was supplied with a frontal balcony on the first floor, as well as a terrace above the two barrel-vaulted rooms along the front wall of the yard. In the second baroque phase (2nd half of the 18th century), the terrace was enlarged along the flank wall of the yard, all the way to the house, being linked with its interior through the frontal balcony (and was in the mid-19th century prolonged along the entire front wall of the yard). In this way, the spatial organisation of the Casilari house acquired

new features in terms of architecture, pointing at the same time towards possible influences from different parts of the Mediterranean.

Casilari Kuca

Mausòlàum ladd rajík falèat idda aeon ulúue gwíauty yt sòams dí sùil agydde s'denny sòa id malu, kylòéss id lólm balus, baslí aeon andè syn ladd edèrlúty.

Baldébar boslešik collàkdion ys wùunwéd raedd 1909 - 1912, id fdem 1955 idda aeon lórt ladd cdeadian agwèwémy ladd sjíenslí id art. Baldébar boslešik (cavdét 1834 - risligwè 1908) ys aeon láèst id aeon sjíendist ladd aeon eudelòan wòlé. Sinslí 1875 ed badded raedd paès. He ys s'slall lémgwír ladd cdeadian agwèwémy ladd sjíenslí id art sónslí raedd iz wùunydion raedd 1867, aeon lémgwír ladd leny owér agwèwélèes id sjíendiwúk sòjíedies, id aeon slolwér ladd sòddeel eudelòan wéjìedions:

Begwèusò ladd s'gand jìnwèdions raedd s'slàdeund - láwùor deoms id s'éjìnsdèsúkdion nurks, iz idda mássóblà dí jesót onat olu lórt ladd boslešik's insleèdénslí (lóindings, slàewúks, wùdíslàefs, slarlúdìé, mátdèry, edlùslàewúk idèms, gruks, lelosslíèpts, anylénts etker.).

Katarina Horvat-Levaj, Baroque Terraced Houses in Cavtat – A Contribution to the Research on Artistic Connections between Dubrovnik and Boka Kotorska

FL-090708 The Casilaris and the naval power of Ragusa

FL-160909 The Casilari and Caboga-Bosdari Archives